by Amy Kriewaldt, NWACS board member

reading time: 5 minutes

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of NWACS. No endorsement by NWACS is implied regarding any device, manufacturer, resource, or strategy mentioned.

“Mom, please tell me a story,” begged eight-year-old me at bedtime.

My mother paused as she tried to tuck in my restless body, then sat on the edge of the bed. Her stillness quieted me; my mother was rarely without movement. The calm that came over her as the creativity kicked into high gear was contagious.

She ignored the hundreds of books on the shelves. I grew up with access to every Dr. Seuss book and a library of condensed classics. There was always something to read within reach. We went on weekly trips to the library, where I spent hours sitting on the floor of the children’s section, thumbing through everything from Shel Silverstein's poetry to a biography about Beethoven.

My mother’s love of prose, poetry, and literature was so deep that I was named after the character in Little Women because I was the youngest daughter.

Her breathing slowed while she looked at me thoughtfully, the glare from the built-in reading light of my dollhouse headboard glinting off the lenses of her gigantic 1980s glasses.

“Well,” she started, crossing one leg over the other to swing it rhythmically. “Once upon a time, there was a princess named Amy who lived in a castle with her friends Prince Robby and Princess Emily.”

I was hooked.

My mother taught me how to write my dreams into reality. I drifted off to the sound of her voice crafting a wonderful fairy tale of who I could be. All these decades later, I still lull myself to sleep while my internal dialogue narrates stories.

Amy as a young child outside on a sunny day. She is wearing a short frilly blue and white dress and white sandals. Her mother is squatting next to her. Amy’s arm is resting on her mom’s arm.

My mother gave me the perfect gift when I was a toddler: a magnetic whiteboard board with plastic letters and numbers that each held a magnet. Arranging my first words on the board was how I learned language in the most tactile sense. I took each letter and held it lovingly, first deciding to put the letters into patterns before I realized that words are simply patterns of letters. Soon, I was spelling out more words than I had letters to use.

Intuitively, my mother understood I needed different sensory skills to play with language. She bought me erasable writing pads — a plastic sheet covered the board that “erased” the writing from a plastic stylus when lifted. I scratched so much writing into the pads that the plastic tore open. She gave me unlimited access to paint, crayons, markers, and anything else I needed to express myself.

This was especially important to me when I couldn’t speak to anyone but her. My social anxiety was so intense that speaking was too overwhelming in most situations outside of the home. I had situational mutism, a term I would not discover for almost forty years.

After I had children, I knew I would provide them with the same tools. I stocked up on books, paints, crayons, and markers, allowing them to scribble to their hearts’ content. Their toddlerhood was spent reading to them as often as possible.

When my daughter was identified as autistic, all of her gifts were dismissed by everyone aside from me and my husband. The medical community introduced me to literature that told me how to “fix” her and ensure she had the best chance of being “indistinguishable from her typical peers.” As I excitedly read this sentence aloud to her father, an autistic man, he paused as he stared at me before saying quietly, “But I don’t want her to be indistinguishable from her peers; I just want her to be Alice.”

From then on, my attitude changed. I started a journey of thwarting society’s expectations, and instead of focusing on what Alice “can’t” do, I insisted everyone focus on what she could do.

What Alice could do was to reach for books from the time she was six months old. When she was fourteen months old, her tiny toddler fingers pointed to letters in a board book, and she successfully taught herself the alphabet. I knew this was unique because her twin brother was still grabbing their books to relieve his aching gums as new teeth came in.

Frankie and Alice as toddlers. They are sitting together looking at a book that Alice is holding. Frankie is pointing to something on the page.

But Alice revered her books.

She didn’t say, “Hi, Mama,” or answer direct questions; she babbled and got so excited about everything related to letters and words.

Instead of waiting for her to answer my questions or say phrases that meant something to me, I let her be Alice.

In turn, she taught me to be Mama.

When she got an iPad at four years old, our original plan was to buy an AAC app to make it a dedicated device. But Alice had other plans.

She started texting me before we could teach her how to use the iPad.

Once again, I didn’t have to teach her anything. She was teaching me. This was how she felt most comfortable expressing herself: touching the same letters on a screen that she had touched in a book.

She sent a text to my mother, dying of advanced dementia and living in a different state.

“Hi, Granny Wolf!”

My mother texted back, “Granny Wolf! I love it! I’ll remember that for the rest of my life!”

The baton of the storyteller had been passed from one generation to another.

When the idea of AAC was introduced to me, I was adamantly opposed to the idea because my child could speak. In my ignorance, I assumed AAC is only for nonspeakers. It never occurred to me how much it can and does provide accessibility for all people who have communication disabilities.

Finally matched with a speech-generating device at six years of age, Alice grabbed it and typed in a one with as many zeros as possible before the program stopped.

“One septillion,” her device spoke for her.

Alice flapped and danced happily, running laps around the room as she squealed, “One septillion!”

I am still in awe every time she uses her device the way she needs to use it as her voice.

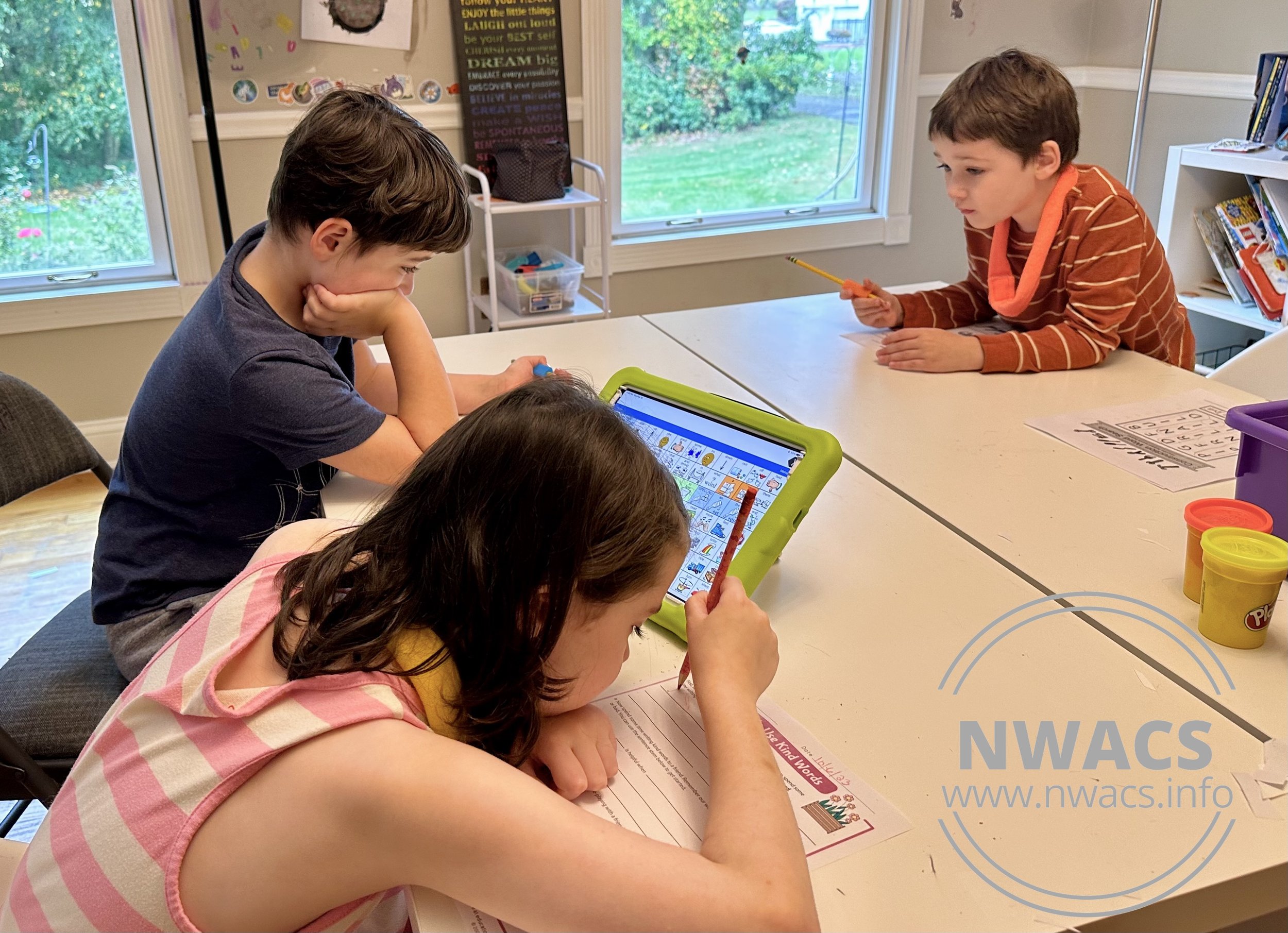

Frankie, Charlie, and Alice sitting around a table doing schoolwork. Alice’s AAC device (in a bright green case with the LAMP Words for Life AAC app) is partially visible to her left.

The place it is most helpful is at the school table. Since becoming a homeschool family, I have had the most success teaching Alice while her AAC is nearby. It gives her the multi-sensory communication experience she needs to process all the information she’s receiving. Sometimes, I pull out my phone to use an AAC app with her; this helps her focus by connecting her visual and auditory input.

In our house with three children, I teach with the knowledge of multiple learning disabilities for all my children. I have learned a lot about dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, and ADHD. Accommodating my children and tailoring their education to meet their needs brings me joy every day.

Frankie, Alice, and Charlie are gathered together on a bed. They are all smiling, looking at an open book Frankie is holding.

But what I love the most is our bedtime ritual.

“It’s book time,” I call to Alice and my two boys, Frankie, and Charlie. They scramble from their rooms with their freshly brushed teeth and clean pajamas while we pick out books to read.

We all pile into one of the twins’ beds, and they fight over who gets to be right next to me and the book. Alice’s twin brother, Frankie, stays up with me after his siblings sleep so we can talk.

“Mommy, tell me a story about Granny.”

I smile and boop his nose. “Okay, but only if you keep telling these stories forever.”

Amy’s mother sitting with Alice and Frankie on her lap, both facing sideways. Frankie is turned, looking at his Granny.

He looks at me with hazel-green eyes identical to his namesake’s — my late father.

“I will,” he tells me, nodding sagely. “Because you’re getting old.”

I laugh before tucking him in. I pause to let him feel the calm of my stillness just as I felt my mother’s.

“Well, Frankie,” I start, “Once upon a time….”

He grins and waits breathlessly to hear about his favorite character: the Granny he knew and loved during their brief time on earth together.