AAC in Adults with Developmental Disabilities

This is a curated collection of information and resources related to supporting augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) with adults with developmental disabilities. We encourage you to explore and judge for yourself which to add to your toolbox.

These resources are for educational purposes. This is not an exhaustive list. Inclusion does not signify endorsement. Use of any information provided on this website is at your own risk, for which NWACS shall not be held liable.

Do you have a favorite resource or strategy that we missed? Send us an email to share!

NOTE: Intellectual and/or Developmental Disabilities (IDD) is a term that covers many disabilities, such as:

fetal alcohol syndrome

intellectual disability

Prader-Willi syndrome

Rett syndrome

Williams syndrome

ADHD

Angelman syndrome

autism

cerebral palsy

developmental disability

Down syndrome

among others.

Developmental disability is a lifelong disability that is evident before the person turns 22. Intellectual disability starts any time before a child turns 18. Often the disability is present at birth. IDD affects the course of the person’s physical and/or mental development. IDD limits the person’s ability to function in three or more of the following areas of major life activity:

self-care

receptive and expressive language

learning

mobility

self-direction

capacity for independent living

economic self-sufficiency

What does supporting communication look like for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities?

When we think of quality of life, we are thinking about psychosocial competence. One’s ability to maintain a state of well-being. To deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life. Going deeper, it is life skills that enable us to manage everyday demands and challenges.

The World Health Organization (WHO, 1994) identified a core set of skills that promote well-being:

decision making

problem solving

creative thinking

critical thinking

effective communication (which includes literacy!)

interpersonal relationship skills

self-awareness

empathy

coping with emotions

coping with stress

These are life skills. Skills in each of these areas provide a foundation for psychosocial competence. These life skills enhance the quality of one’s life. These are universally needed and/or desirable to be a full participant in everyday life.

When we look even deeper, we realize that ALL the communicative competencies are needed to develop these life skills:

linguistic competence - receptive language (including text-based), expressive language (including text-based), vocabulary, grammar, morphology, etc.

operational competence - skills needed to use the AAC system, including navigation and adjusting volume

social competence - skills that support making and keeping relationships

strategic competence - skills to fix communication issues and increase communication effectiveness

psychosocial competence - motivation, attitude, confidence, resilience, etc.

emotional competence - being able to identify, respond to, and manage own emotions as well as the emotions of others

All the communicative competencies support well-being and quality of life.

People with IDD reach adulthood with a range of communication skills. Their communication abilities may be emerging. Or they may be able to communicate independently. Some adults with IDD do not have a reliable way of communicating using symbolic language. They may have developed unique, unconventional ways of communicating. Other adults with IDD use symbolic language to communicate anything to anyone in any situation. They may even be able to read and spell.

What does supporting communication look like for this age group? It looks like meeting the person where they are at and helping them build on their strengths. It looks like continuing to support their development of language, literacy, communication, and other life skills. It looks like supporting the goals they have for themselves.

Wait and be patient!

“Most important is: be patient! And not interrupt while they are still using AAC device to say something. Talking with AAC device is always more slow than mouth talking. Even the best AAC user with the best AAC device will still need more time and patience than mouth talkers.

Many times AAC devices do not have exactly the right word a person needs. May need to look for a longer time to try finding a suitable replacement word. For example when C. wanted to talk about a specific kind of place but didn't have the right word, C. said “death park”. With a little bit of thought the person understood that C. was trying to say Cemetery!

A person's way of using an AAC device, and how fast or slow a person is, have not much to say about a person's ability to think and understand.

Really is so important to keep waiting with patience!” ~ C., AAC User

Read more about providing AAC users opportunities to take turns in conversations and discussions: Let’s Talk AAC: More About The Right to Make Comments and Share Opinions

Be a good communication partner.

“I feel the key to good communication is having skilled communication partners.” ~ Beth Moulam, AAC User (on her blog)

An important part of supporting communication for this age group is by learning how to be a good communication partner. Good communication partners do the following:

ensure access

presume competence (making connections)

accept all forms of communication

pause and wait

listen actively

clarify and confirm

be respectful

model and coach

Read more about being a good communication partner: Let's Talk AAC: The Right To Access Environments and Interactions as Full Communication Partners (Communication Right #12)

Continue working on communication skills.

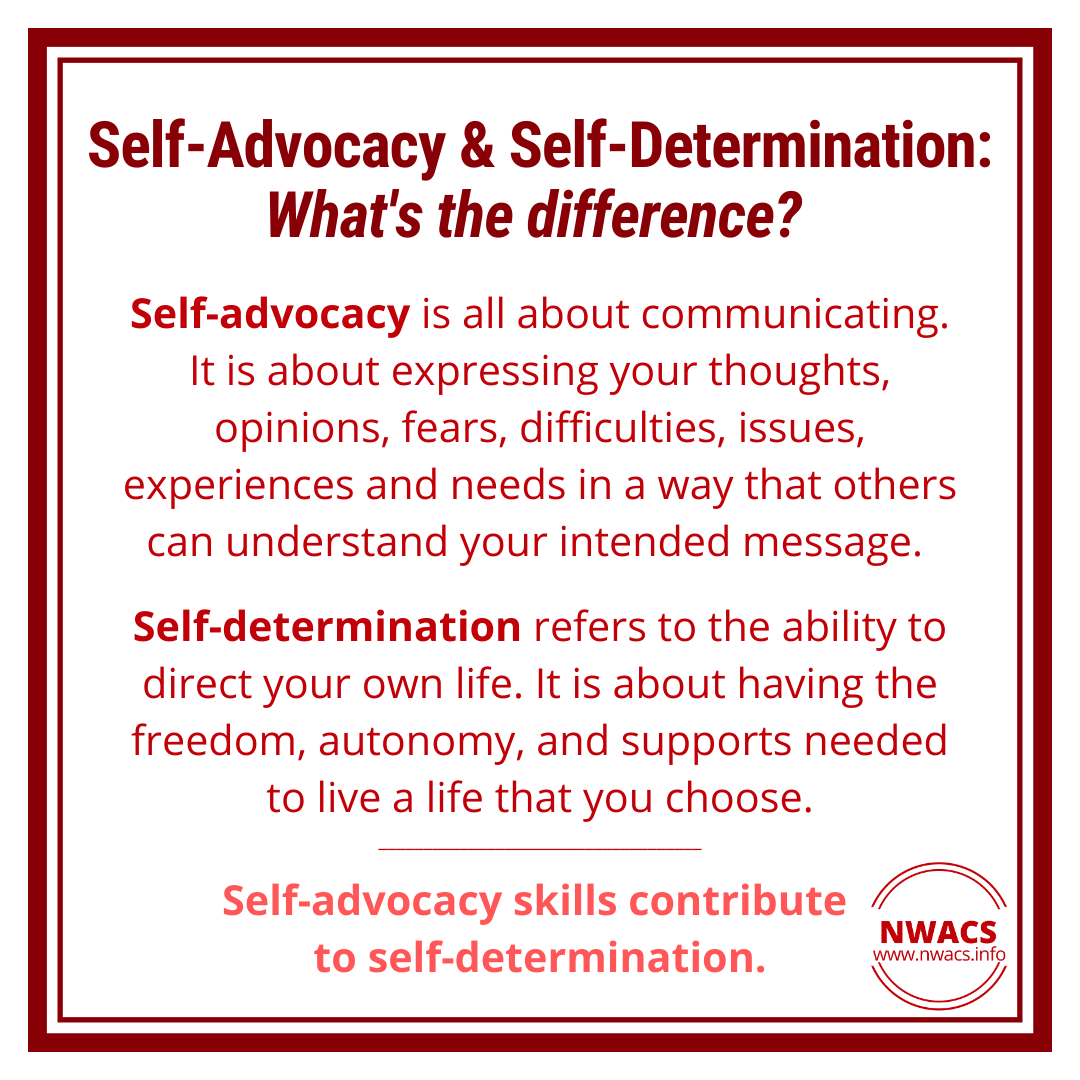

It is important to continue developing communicative competence. To be a full participant in daily life, to self-advocate, and to have self-determination, a person must have autonomous communication! Human beings have the capacity to learn even in adulthood.

It bears repeating. Many, if not most, agencies and organizations that provide job help to disabled adults look for the disabled person to have strong independent communication skills. Even many adult day programs need the people attending their program to be able to communicate without caregiver help. This is unfortunate. Many disabled adults who can successfully (and autonomously) communicate using partner-assisted methods, may not have the physical capacity for completely independent communication.

Age-related changes.

“We have largely achieved the goals of integration in terms of where the disabled live. But we have fallen short of those goals in terms of how they live.”

As people with IDD become adults, there are new age-related issues that influence communication and AAC use, as well as quality of life.

Often young adults age out of the school system without an AAC system they own, leaving them without an AAC system as an adult.

There are still many adults that have no or limited history of AAC use, which means they have developed a lifetime’s worth of behaviors and unique signals that serve as their primary means of communication. They may have also developed learned passivity and lack of interest in using AAC based on their life experiences.

If the adult does have an AAC system, often there is limited appropriate vocabulary available to them.

Some adults with IDD are emerging communicators. Emerging communicators of any age can be tricky! Some seem to show little response to or interest in interacting with others. Most communication partners are not taught how to engage older emerging communicators.

The majority of communication partners in adult settings have a lack of AAC knowledge and training. So if the adult relies on a communication partner to assist with their communication, communication gets abandoned.

There is a huge lack of SLP, PT, OT support in adult day or residential programs. Many adults go YEARS without appropriate support of communication tools.

Available SLPs, OTs, PTs often lack AAC expertise, which often means no focus on AAC.

Adults with IDD will age and likely face health care issues - both their own and related to their aging parents. Aging means potential need for modifications to AAC systems and/or new AT equipment or interventions to accommodate new developing issues (e.g., arthritis, vision issues, hearing loss, cognitive changes, etc.).

Key Goals

“I am a human being, not a human doing, not a human island. I am interdependent. So I need help with some things, OK maybe a lot of things. Also, I am helpful and worthwhile to others in some other things, because that is the real meaning of life.”

~ Elizabeth (Ibby) Grace (from the blog post ‘I Am Not Independent.’)

the person’s goals

self-advocacy

self-determination

communicative competence

literacy skills

work and leisure activities

developing, maintaining, and sustaining social networks

supportive and effective communication partners

What AAC Looks Like

multimodal

allows them to fully communicate about anything in all environments with all people they encounter

matches the access needs and other features needed by the adult

Helpful Strategies

ask the AAC user how you can be a good communication partner

provide enough wait time

be flexible

ensure AAC options are always available

accept all forms of communication

presume potential/competence

communication is more about social closeness (building and maintaining relationships)

support conversation skills and strategies

adults need language and skills related to

physical, mental, emotional, sexual health (including sex education)

boundaries, consent, healthy relationships

medical, disability, care needs

safety, abuse, rights

learning never stops!

use supports and strategies based on the communicator’s strengths, needs, likes, and interests; implementation strategies such as those mentioned on our AAC in School-Age resource page may still be useful

Resources to Explore

Articles, Books, and Documents

AAC for All: Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Practice (2022) by Mollie Mindel and Jeeva John

Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Challenges and Solutions (2021), Billy Ogletree

Chapter 9: Challenges in Providing AAC Intervention to People With Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilties by Jeff Sigafoos, Laura Roche, and Kathleen Tait

Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Engagement and Participation (2017) by Erna Alant

Fundamentals of AAC: A Case-Based Approach to Enhancing Communication (2023), Nerissa Hall, Jenifer Juengling-Sudkamp, Michelle L. Gutmann, and Ellen R. Cohn (eds)

Let’s Talk AAC: More About The Right to Make Comments and Share Opinions (2022) NWACS blog

Let’s Talk AAC: The Right To Access Environments and Interactions as Full Communication Partners (2022) NWACS blog

Let’s Talk AAC: The Right To Have Communication Acts Acknowledged and Responded To, Even When the Desired Outcome Cannot Be Realized (2022) NWACS blog

Let’s Talk AAC: The Right To The Accommodation of Time (2022) NWACS blog

Supported decision-making when you cannot speak, AssistiveWare blog

TalkingMats: “A Talking Mat is a visual communication framework which supports people with communication difficulties to express their feelings and views.”

Washington State Division of Vocational Rehabilitation (DVR)

Webinar Recordings

AAC in the Cloud presentation recordings:

AAC and Self-Determination - Autonomy and Safety in Home/Community-based Services by Courtney Johnson (2023)

AAC in the Workplace by D. Burrow (2019)

Powerful Insights from Adult AAC Users That Challenge How We Practice AAC by Amanda Hartmann (2019)

Symbols, Multimodal Communication and Screen Readers - Adapting AAC and Reading and Cognitive Support Needs in Adults by Saoirse Tilton (2021)

Taking My AAC Into Adulthood by Cristian Rosas (2021)

UCF AAC Collaborative webinar recordings

Other Resources

OCALI Assistive Technology Internet Modules - AT for Adults and Adults with DD

Useful Tips

Provide time, patience, and more time, and more patience! Intentionally create space in conversations and discussions for AAC users to be able to take a turn and be an active participant!

Communicating through an AAC system - even the most robust, best-fit system - is slow and hard.

Beware of ableism and infantilization!

Adult AAC users are adults and deserve to be treated as the adults they are.

Adult AAC users deserve the dignity of risk.

Adult AAC users deserve to be heard. They deserve to make decisions and direct their life.

Communication partners need training and ongoing support!

Focus on communication intent, not how the message is communicated.

Find your support networks!

AAC Users:

ISAAC PWUAAC Online Chats - The International Society for Augmentative and Alternative Communication (ISAAC) invites people who use AAC to meet online for informal chats. Check their website and/or their social media for dates and times.

Facebook groups:

Ask Me, I’m An AAC User! (24-Hour Rule!) is a Facebook group run by AAC users where the thoughts and experiences of AAC users in the group are the focus

AssistiveWare’s Adult AAC Users Community is a Facebook group for adults who use Proloquo2Go and/or Proloquo4Text

Out and About: Creating Community Groups for AAC Users is a community group on Facebook for people of any age who use AAC

The AAC Connection is a Facebook group for AAC users, family members, and communication partners

There may be other groups centered around your AAC device or communication app where you can connect with other AAC users.

Other:

Seattle Children’s Alyssa Burnett Adult Life Center offers virtual and in-person classes and outings for people 18 and older with developmental disabilities

[Skagit County, WA] Cascadia Clubhouse offers recreational activities for adults with developmental disabiltiies

Families / Caregivers / Support Staff:

AAC vendors and app developers have pages on various social media channels. Many also have Facebook groups that can be a good place to connect with a support network.

also look for social media accounts and/or Facebook groups related to specific diagnoses

and look for social media accounts of AAC users and/or parents of AAC users

Professionals:

NAACHO: Networking for AAC and Hangout - This Facebook group (administrated by NWACS) is for SLPs in Washington State who support people who use AAC. It is for collaboration, networking, and supporting each other in the grand adventure of augmentative and alternative communication.

Also be on the lookout for in-person NAACHO events (hosted by NWACS)!

AAC vendors and app developers have pages on various social media channels. Many also have Facebook groups that can be a good place to connect with a support network.

also look for social media accounts and/or Facebook groups related to specific diagnoses

and look for social media accounts of AAC users

Facebook groups, such as:

Selected References:

ADA Requirements: Effective Communication, U.S. Department of Justice (2020)

Article 21 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, United Nations (2006)

Bagenstos, Samuel R. "The Disability Cliff." Democracy 35 (2015): 55-67. Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/1722

Brady, Nancy & Bruce, Susan & Goldman, Amy & Erickson, Karen & Mineo, Beth & Ogletree, Billy & Paul, Diane & Romski, MaryAnn & Sevcik, Rose & Siegel, Ellin & Schoonover, Judith & Snell, Marti & Sylvester, Lorraine & Wilkinson, Krista. (2016). Communication Services and Supports for Individuals With Severe Disabilities: Guidance for Assessment and Intervention. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities. 121. 121-138. 10.1352/1944-7558-121.2.121.

Developmental Disabilities Act of 1984 (Public Law 98-527)

Disability Rights Washington: Six Self Advocacy Steps for Meetings

RCW 71A.26.030 Client rights—Notification.

WAC 284-43-5965 Effective communication for people with disabilities.

White, R., Bornman, J., & Johnson, E. (2015). 'Testifying in court as a victim of crime for persons with little or no functional speech : vocabulary implications', Child Abuse Research: A South African Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1-14. URI: http://hdl.handle.net/2263/49693

World Health Organization. Division of Mental Health. (1994). Life skills education for children and adolescents in schools. Pt. 1, Introduction to life skills for psychosocial competence. Pt. 2, Guidelines to facilitate the development and implementation of life skills programmes, 2nd rev. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/63552